WVU researcher delves into cardiovascular effects of vaping

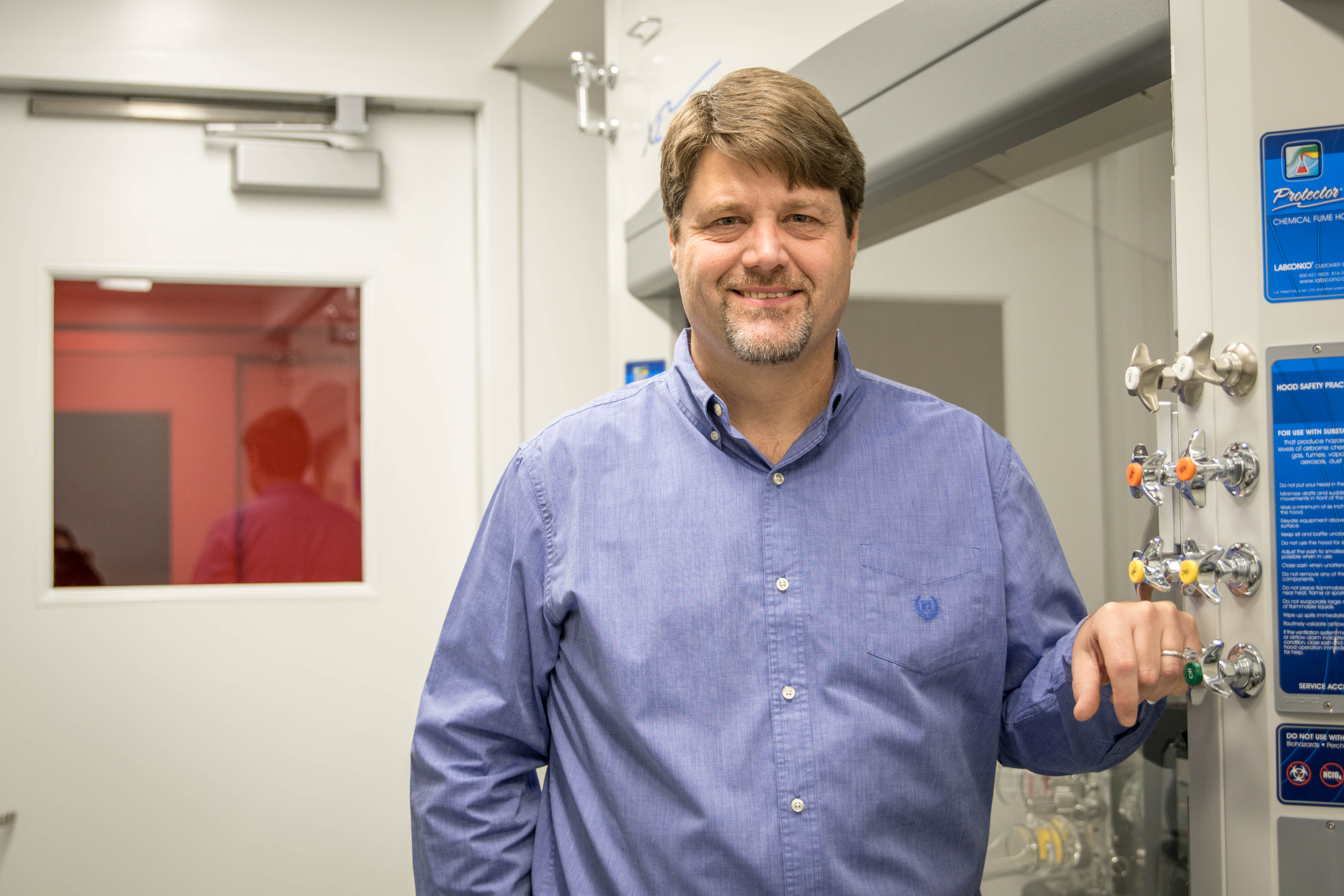

Vaping has surpassed all other forms of tobacco use in middle- and high-schoolers. New research led by Mark Olfert, an associate professor in the West Virginia University School of Medicine, suggests if teenagers continue to vape into adulthood, the cardiovascular effects may, by some measures, be as dire as if they’d smoked cigarettes.

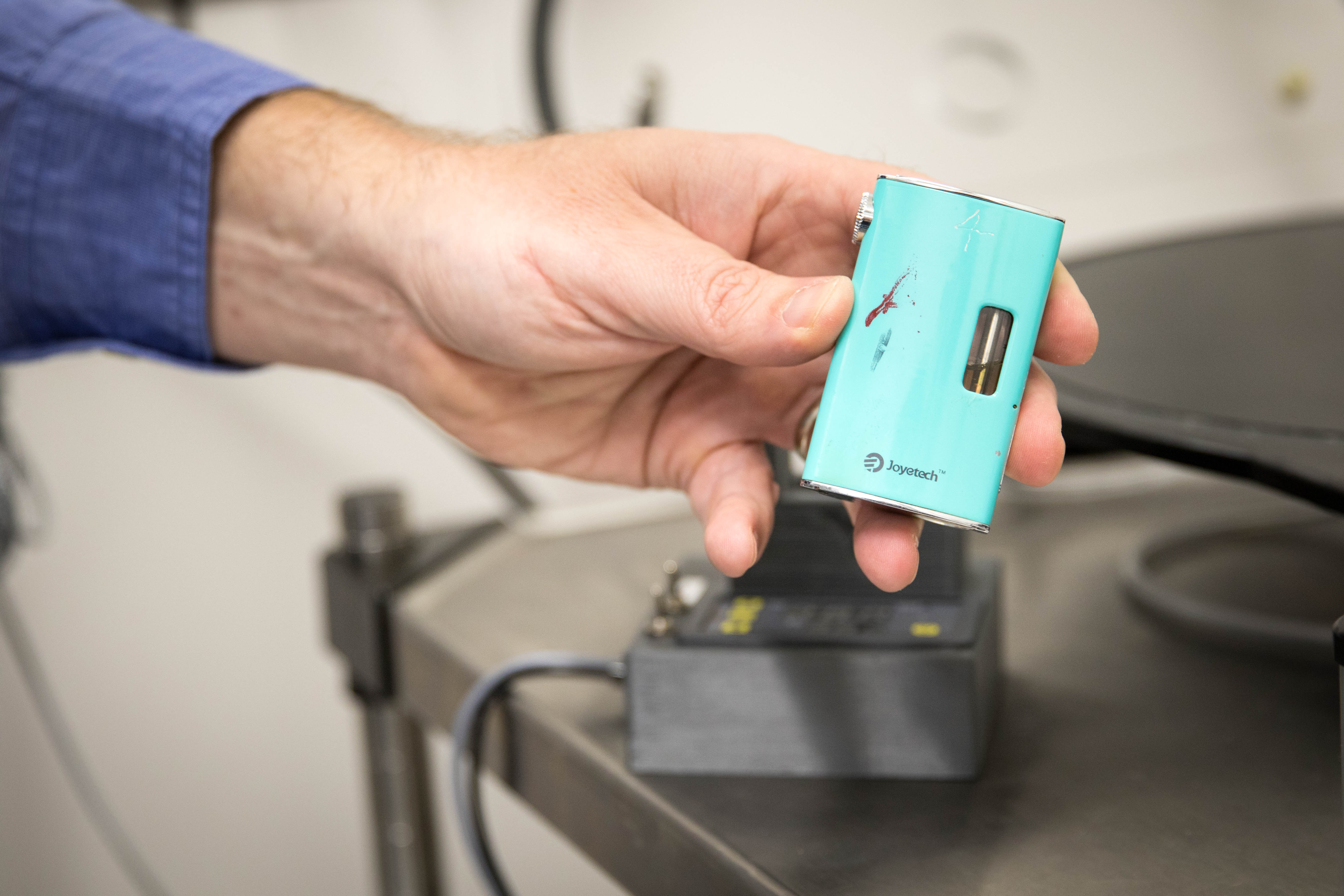

Flavors like blue raspberry, birthday cake, root beer float and honey nut cereal are just some of the flavors that vapers can add to make e-cigarettes more appealing to younger consumers. But virtually all e-cigarettes contain a similar base solution that often includes nicotine.

Over eight months, Olfert and his colleagues exposed animal models to four hours of this e-cigarette base solution, five days a week. “That’s the equivalent of 25 years in humans,” Olfert said. The research team exposed other models to cigarette smoke for the same duration. A third group of models served as a control and was exposed to clean air.

The researchers found that chronic exposure to e-cigarette vapor stiffened the aorta (the body’s main artery) 2.5 times more than the regular aging process did in a vape- or smoke-free environment. In comparison, cigarette smoke caused a 2.8-fold increase.

Olfert describes aortic stiffness as an “early warning sign” of cardiac and vascular-related diseases, which can include atherosclerosis, stroke and aneurysm. “Stiff vessels can be like that old rubber band that sits in a drawer for long time, and they can lead to many problems,” he said. For example, the research showed that chronic vaping reduced the aorta’s ability to relax by 25 percent in animal models. Chronic smoking reduced this function by 33 percent.

The Journal of Applied Physiology published the results earlier this year. “Until that paper came out,” said Olfert, “there simply was not any long-term study evaluating the chronic effects of vaping on blood vessel function.” Short-term studies in people also show early signs of changes in vascular function, but the evidence for disease that stems from chronic use will take much longer to determine. “So far, people have only been exposed to e-cigarettes for about 10 years. This is likely going to take 20 to 30 years to manifest, just like with cigarettes.”

That means adolescents who take up vaping today may not see the habit’s cardiovascular effects until they’ve finished college, launched a career and secured a mortgage. In the meantime, scientists are relying largely on animal models to gather and interpret data on vaping’s health effects. Long-term human studies aren’t available yet.

Olfert’s findings take on added significance in light of the Food and Drug Administration’s crackdown on teen e-cigarette use. He pointed out that the recent U.S. Surgeon General’s report on e-cigarettes indicates that e-cigarettes have now surpass all other forms of tobacco use among middle- and high-schoolers.

Olfert is also troubled because the number of e-cigarette users between the ages of 18 and 24 now exceeds the number of e-cigarette users who are 25 and older.

“Our real concern is what happens with the younger generations, particularly in the context of the unknowns,” he said. “The data we’ve generated in the lab, using animal models, are suggesting that e-cigarettes are not safer than cigarettes with respect to the blood vessel health. Simply put, we’re seeing the same degrees of dysfunction between e-cigarettes and smoking.”

Citation

Title: “Chronic exposure to electronic cigarettes results in impaired cardiovascular function in mice”

Publication: “Journal of Applied Physiology.” 2018;124:573–582.