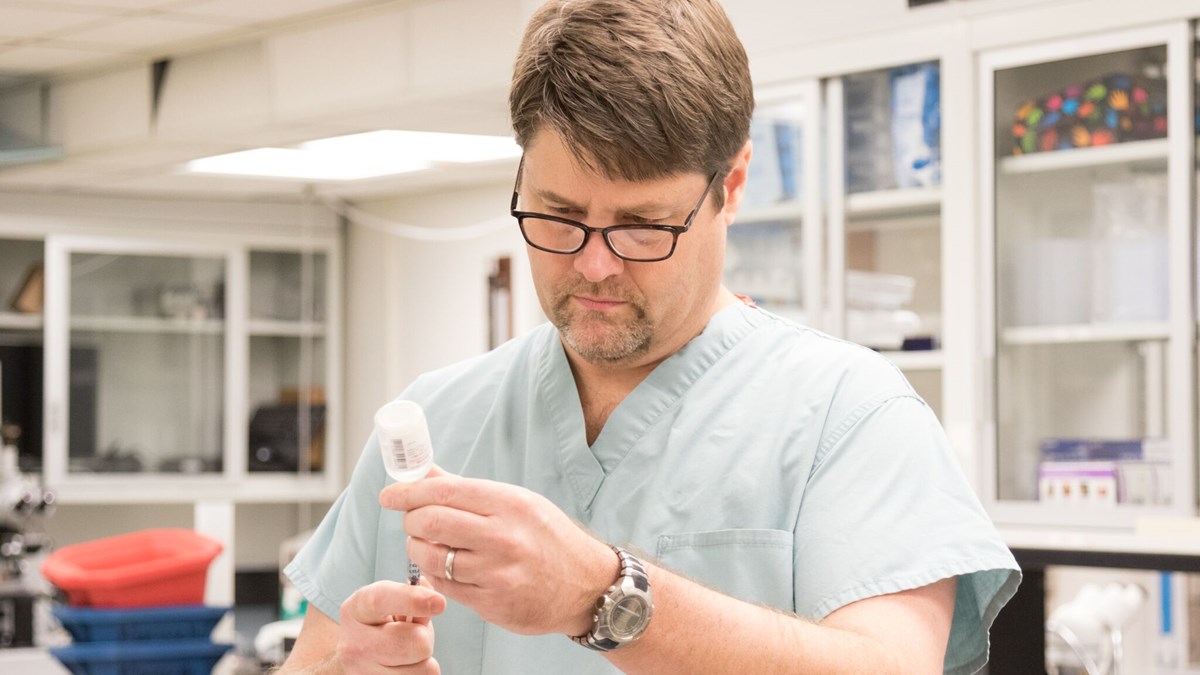

Mark Olfert, Ph.D.

“I think using a multi-disciplinary team to address complex problems like obesity is essential, and this approach is what makes it so impactful.”

WVU scientist brings national attention to Appalachia health problems

When Mark Olfert, Ph.D., F.A.H.A., embarked on his academic journey, he thought he wanted to become a physician. He was ahead in his career as a respiratory therapist, spending most of his time in the neonatal intensive care unit, when a pivotal moment changed his future.

“I got involved in a research project that one of the ICU physicians was conducting, and as soon as I started, I was hooked to research,” Dr. Olfert said. “Then I had to decide whether to continue pursuing my medical degree or consider research as a career. I ended up going the research route.”

Although Dr. Olfert's training was in the basic sciences field, he wanted to combine his clinical background to his research interests.

“Clinical translation is very natural for me because a lot of my projects typically study the whole animal,” he said. “That’s part of what excites me about science – figuring out the physiology, the connection of the whole organism to any response that we change or can create.”

After more than two decades in California, with more than half of those years spent at the University of California-San Diego, Dr. Olfert and his wife, also a professor at West Virginia University in human nutrition at Davis College, moved to Morgantown, a place he praises for various reasons.

“West Virginia is a beautiful state,” Dr. Olfert said. “I enjoy having seasons; I moved here for the weather, and that’s the joke that I am using, since San Diego has very little change in the weather. WV is also a great place to raise a family, and we have a daughter so we’re enjoying the beauty and the life that West Virginia has to offer.”

In his office, a picture of blood vessels twisting through skeletal muscles hangs on the wall facing his desk and cannot go unnoticed.

“I have spent 15 years of my career studying the regulation of angiogenesis, how blood vessels are formed, in an attempt to understand why people with chronic heart and lung disease begin to lose blood vessels in their muscles and organs,” he said. “This leads to secondary problems as it it impairs their ability to exercise, and exercise intolerance is a key indicator that is associated with increased mortality.”

According to Olfert, one definition of an improved quality of life is to decrease the chances of getting or advancing disease. Thus, he continues to use new and different strategies to model disease and understand how to fight these complex and challenging processes.

“Part of the backbone of sciences is understand normal biology and physiology," Dr. Olfert said. “In time, either in my own work, or decades from now, we hope our findings can eventually lead to treatments, cures or ways to help patients with chronic disease.”

Switching gears to Olfert’s research projects, two of them are currently underway in his lab at West Virginia University, both of which touch on national problems where West Virginia takes the lead: smoking and obesity.

In his first project, dubbed, “Mechanisms of pulmonary and cardiovascular dysfunction to acute and chronic exposure to environmental pollutants, such as cigarette smoke, e-cigarette vapor, nicotine, and engineered nanomaterials,” Olfert is studying e-cigarettes to understand the risks and harms so that he can fulfill the imperative need to inform health care providers and the public.

“The fact that e-cigarettes might have fewer toxicants compared to regular cigarettes makes people think they are safer, and subsequently better to smoke than regular cigarettes,” he said. “But, fewer toxicants is not necessarily ‘safe’ or ‘safer’, because it only takes one of these chemicals to cause harm. This is a perspective many people who are vaping are not considering."

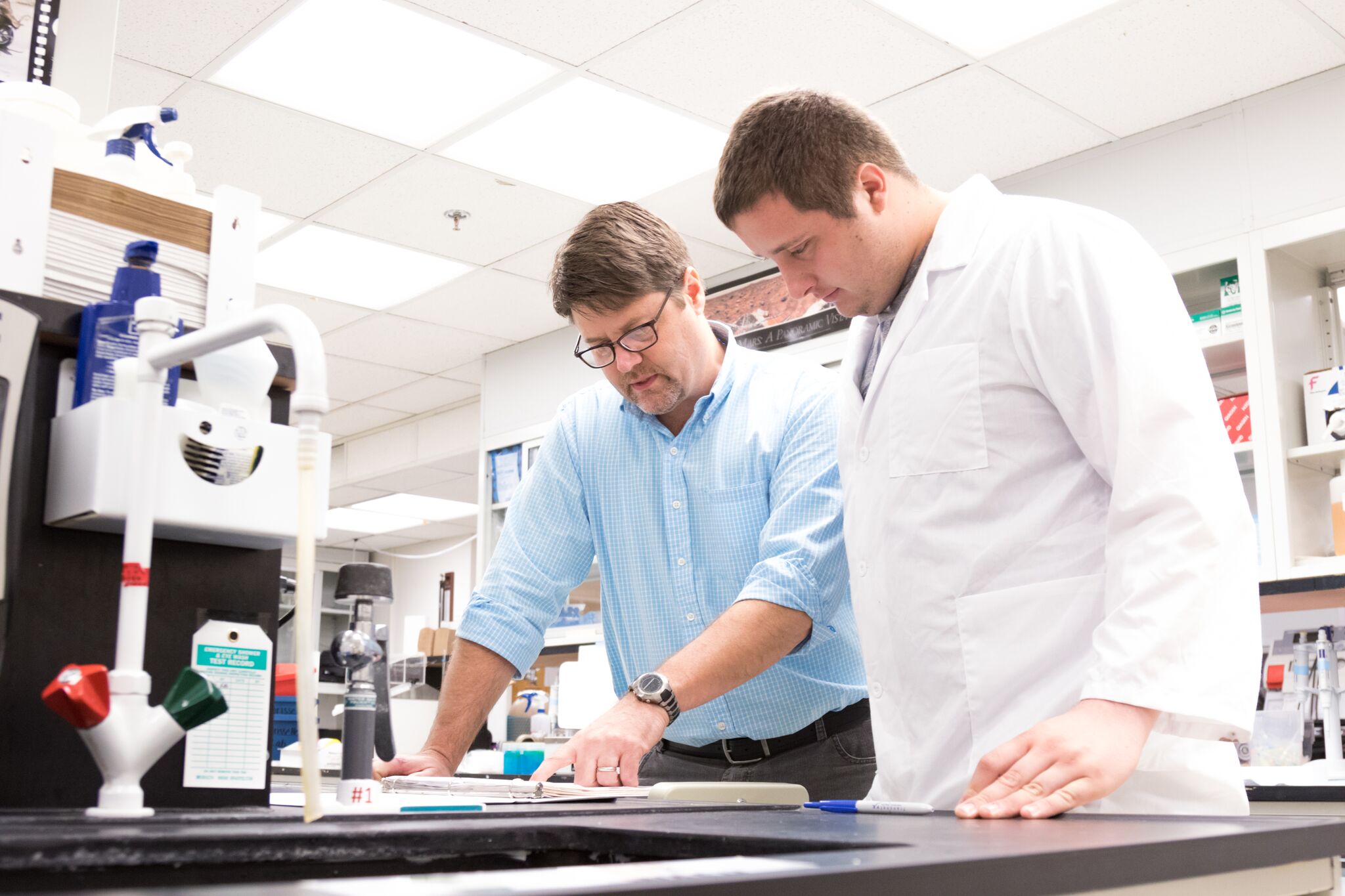

Dr. Olfert is also one of several faculty members who are working together on the the “FRUVEDomic” project, a term coined to describe and study the impact of fruits and vegetables consumption by using cutting-edge omic-based technology to investigate changes in the metabolome, microbiome and cardiovascular health.

Asked about the impact of this particular project on the public, Dr. Olfert elaborated that obesity and complications that follow it are a huge problem for our nation and in particular the Appalachian region. Thus, there is a fundamental need to better the mechanism of how nutrition and the food we eat contribute to obesity and its impact to chronic disease.

“So far, the outcomes seem positive," Dr. Olfert said. "In the first phase of the study, which involved mostly healthy people who were eating poorly and at risk in developing metabolic syndrome, we see small, but significant improvements, in metabolic and vascular health. In the second phase, we are currently studying young adults who have metabolic syndrome and hope to see much bigger benefits. This part is still on-going, but it is something that should be very tangible from the public health point of view, because it represents a real life intervention that most people can follow to improve their health and reduce the risk of disease."

Dr. Olfert is a strong proponent of multi-disciplinary research. The FRUVEDomic project is a testament to his approach, as it involves faculty from two colleges and six different department at WVU, including human nutrition, animal biochemistry, microbiology, exercise physiology, pediatrics and laboratory medicine, not to mention over a dozen students at all academics levels.

“I think using a multi-disciplinary team to address complex problems like obesity is essential, and this approach is what makes it so impactful,” he said. “When you work across disciplines, it broadens your own horizon and I believe helps to develop a more meaningful project because you get different perspectives of science, as well as personalities, and that makes the data and the project far more valuable.”

Throughout Dr. Olfert’s work and research projects, one thread seems to stand out – his passion and relentless pursuit of seeking to ask the right questions to understand how things work. A trait he labels as the most important for prospective researchers.

“I tell all my students that research is 90% boring, and I think that’s true for the most part, since the mechanics of doing research is often very repetitive and often not exciting, but what makes research exciting is when you are pursuing something with passion,” Dr. Olfert said. “Getting that piece of information and how we interpret it is the exciting part. Perseverance is also something that you must have, and if you really care about the question, it comes naturally. Schooling and mentors can teach a student how to design the study, develop the protocols and procedures, but they cannot teach passion and perseverance."